China’s multi-decade long, successful effort to plant a ring of trees around one of the world’s most hostile deserts has sprouted an unexpected benefit to humanity.

Along with protecting the nation’s grasslands and agriculture from the spreading sands of the dismal Taklamakan Desert, the giant ring of trees has turned previous unproductive land into a carbon sink that draws CO2 out of the atmosphere.

It’s thought, and some isolated research has indeed demonstrated, that humans can prevent the worst effects of a rise in average global temperatures by planting trees to absorb more CO2 from the atmosphere.

This strategy has limits, however, when viewed on a global scale. Atmospheric CO2 levels continue to rise, while there is a limit in the amount of land that can be turned over to forests.

One-third of our planet is covered in deserts, where vegetation is sparse or absent, and rainfall is scarce, yet despite their vast acreage they collectively hold less than one-tenth of the world’s carbon stock, or the amount of carbon that is held underground.

A study conducted by NASA and California Technical Institute (Caltech) has used satellite data to demonstrate that the “sea of death” as the Taklamakan Desert was called in antiquity, could be utilized to store carbon and reduce the greenhouse effect.

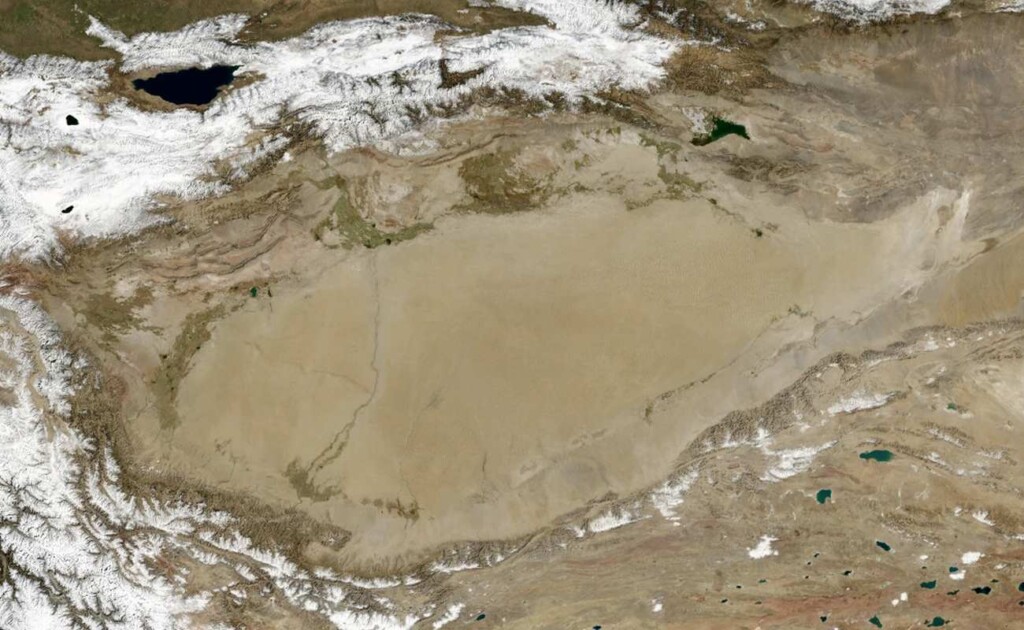

Starting in 1978, China’s Three-North Shelter Belt program aimed to plant trees along the borders of the great Taklamakan to stop sandstorms from ruining adjacent pasture and agriculture land. As the world’s single farthest point from any ocean, the Taklamakan is one of the driest and most hostile landscapes on our planet.

The massive Himalayas rise to the south and east, the Pamirs to the southwest, and a pair of mountains known as the Tian Shan and the Altai to the west, leaving landscape completely isolated from moisture.

66 billion trees have been planted by estimates since the start of the Shelter Belt program, which finished in 2024. Monikered the “Green Great Wall,” this incredible increase in greenery has raised average rainfall by several millimeters, resulting in a natural growth of foliage during the wet season that boosts photosynthesis along the tree line, leading to greater degrees of sequestration.

TRANSFORMING OUR PLANET:

“We found, for the first time, that human-led intervention can effectively enhance carbon sequestration in even the most extreme arid landscapes, demonstrating the potential to transform a desert into a carbon sink and halt desertification,” study co-author Yuk Yung, a professor of planetary science at Caltech and a senior research scientist in NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Live Science in an email.

By precise numbers, it has reduced the average carbon content in the desert air from 416 parts per million to 413 ppm. Parts per million is used as a measurement for the greenhouse effect. Worldwide, the number is 429.3. It was 350 in before the advent of industrialization.

If more shelter belt-style tree planting efforts could be used to reclaim desert landscapes, it could open vast areas to absorbing carbon. With little to no vegetation, deserts in their natural state have precious little ability to do so.

SHARE This Global Impact Of This Beyond Ambitious Attempt To Contain A Desert…